Since the early 1990’s, Sierra Pacific Industries (SPI) has bought out all of its competitors in the region, becoming the largest private timberland property owner in California. SPI began systematically applying widespread clearcutting, followed by bulldozing, herbicidal “site prep” treatments, and tree planting that converted the diverse natural forest into 20-acre blocks of tree plantations. These plantations reduce the forest's genetic diversity, increase fire risks, and reduce carbon storage, among other effects.

Private forest logging practices

CSERC supports thinning logging methods by private companies on their private lands as a sustainable practice, but we strongly oppose clearcutting.

On some sites, SPI has softened the visual impact of clearcuts by leaving a scattering of small trees or a few pockets of tree clumps. Even in those situations, more than 95 percent of each 20-acre clearcut unit is still logged, bulldozed, sprayed with herbicides, and converted to even-aged tree plantations that lack diversity.

The diverse and healthy forest habitat that originally grew on those sites is mostly destroyed, and the remaining healthy forest adjacent to the clearcut units ends up being severely fragmented. Many wildlife and plant species struggle to survive in the limited habitat created by uniform rows of densely-planted pine trees. CSERC continues to advocate for changes in California’s private land logging practices.

This short video features local scenery, insights into the harms of clearcut logging practices, better solutions, and what you can do to help!

The environmental effects of a clearcut

Clearcutting does more than leave an unpleasant visual impact; the forest ecosystem is extensively degraded.

The clearcut logging method involves first removing all the profitable saw-log-sized trees on a forest site. Then, the logged sites are often bulldozed to clear the site of shrubs, young trees, and other plants that might compete with the next crop of conifer seedlings.

Usually, herbicides are then used to kill any grasses, bushes, and groundcover plants that may survive the bulldozing. Many sites end up completely sterile, without wildflowers, groundcovers, oaks, or other plants. A natural forest contains hundreds of plant species besides conifers. Plants such as the endemic Fivespot flower shown below can be completely eliminated from an area by herbicides.

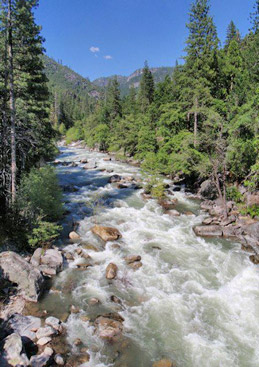

The now exposed soils on the now denuded hillside are often prone to erosion during heavy winter rains or spring snowmelt. Topsoil can wash off the clearcut into downslope streams and rivers. Skid trails also form gullies that funnel water and eroded sediment into streams. Large trees, snags, and downed logs that normally create refugia habitat when they fall into streams are no longer present. The originally diverse forest is converted into a uniform tree plantation- a far less productive environment for the native plants and animals that are part of the forest ecosystem. These monoculture tree plantations have low genetic diversity, making them less adaptable to droughts, climate change, and disease; while also creating more hazardous fire conditions.

Clearcutting on an unprecedented scale

Despite the fact that logging has been occurring in the Northern Yosemite region for 150 years, the scale of forest clearing and SPI’s conversion of the forest to sterile tree plantations is unprecedented. In some subwatersheds, SPI has cleared as many as 3,000 acres within a decade. Overall, tens of thousands of acres of forest have already been clearcut.

Each year new Timber Harvest Plans by SPI result in additional clearcuts or similar even-age type logging treatments. The sheer magnitude of clearcutting has profound effects on wildlife, water, and scenic resources.

Blue Creek Watershed North of Highway 4

South Fork of the Mokelumne Watershed

Clearcuts threaten watersheds

If just a single 20-acre clearcut is logged, it may not affect water quality. When many large sites are clearcut each summer and fall within the local region, these widespread disturbed areas have a cumulative effect that can pollute many forest streams with sediment.

The next time there are heavy rains, take a drive into the national forest and look at streams flowing off the private timberlands. The streams flowing from recently cutover areas are often brown with sediment whenever heavy downpours flush soil down the steep, denuded slopes. Sediment-choked streams and rivers have a negative impact on water quality for people as well as a diversity of aquatic and plant species that depend on clean and clear water to survive and reproduce.

Selective thinning instead of clearcuts: a win-win solution

CSERC has consistently supported thinning logging projects within the Stanislaus Forest, especially when extra protection is provided for wildlife. Our staff recognizes that frequent wildfires historically kept many areas of the forest open and park-like. Without frequent low-intensity fire, forests have become choked with thickets of understory and medium-large trees. Not only do densely stocked trees compete for limited moisture during dry years, but they can also serve as ladder fuels that carry flames into the canopy of mature, overstory trees. Scientific studies of historic forest conditions have identified healthy forests as having lots of scattered individual trees along with frequent openings and frequent patches of denser groups of trees.

Using science-based thinning logging can open up overgrown forest areas while leaving all of the larger trees for wildlife and scenic values. The Forest Service can provide wood for the American people in an ecological way that actually improves, rather than harms, forest health. Not all areas in the forest should be managed by thinning logging treatments, but applying such projects to the areas with the least environmental constraints can lead to middle ground benefits to the forest environment as well as to the local economy.